The Brazilian nation was constituted through successive layers of miscegenation among multiple Indigenous, European, African, and, more recently, Asian communities which, upon encountering and confronting one another, gave rise to a cultural universe at once multiple and singular. This process, far from linear, unfolded within a matrix of power asymmetries and relations of domination. Yet it is precisely within this entanglement of conflicts, resistances, and negotiations that fertile exchanges and hybridizations emerged, forging a cultural fabric of irreducible singularity. Today, Indigenous cosmologies converse with African and European traditions, shaping a syncretic spirituality where Orixás intertwine with Catholic saints, shamanic rituals coexist with popular processions, and symbols circulate and transform reinventing themselves in a profoundly Brazilian language. This plurality, though embodying an ideal, long struggled to achieve recognition.

A Memory in Metamorphosis

Art history, as written by Western institutions, rests on a selection of memory processed by elites of patriarchal and colonial societies, who imposed their narratives as the only legitimate channels of knowledge transmission. Thus, memory, for a long time reduced to a mere historical archive of civilizations, is now considered a process of constant reconstruction, founded not only on facts but also on interpretation and the power of imagination. In Brazil, this selective process of memory became one of the key instruments of colonial hegemony: it imposed itself through the invasion of territory, the violent domination of Indigenous peoples, the enslavement of African populations, and the brutal imposition of European culture. Domination was exercised not only through force, but also through the systematic erasure of origin stories, images, and cosmogonies. It therefore becomes necessary to analyze the role of artists in this dynamic, both for their contribution to the reconstruction of collective imaginaries and for their capacity to reverse an implicit and diffuse form of censorship.

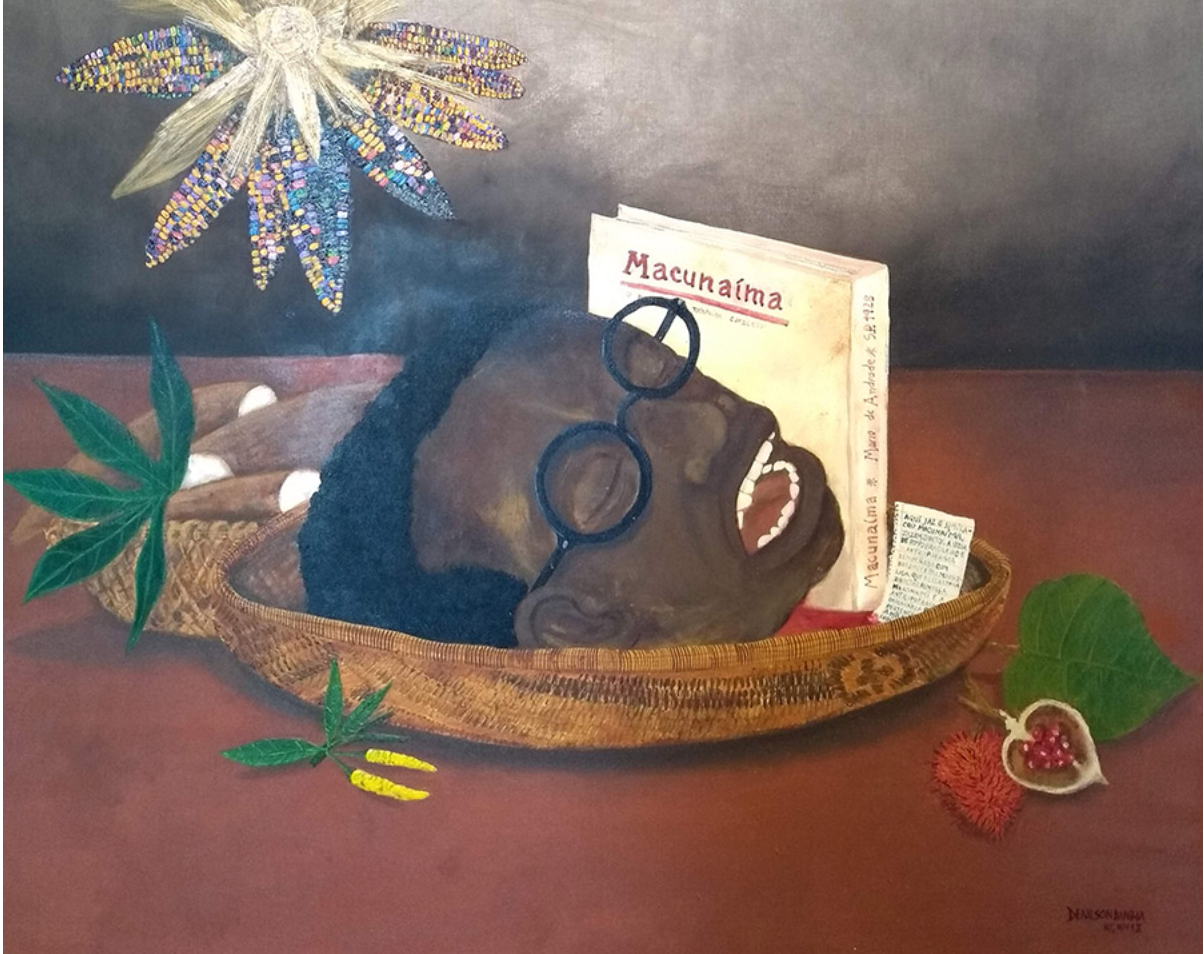

In this logic of resistance, the Anthropophagic Manifesto of 1928 proposed to “devour” European culture in order to transform it into an authentically Brazilian expression. A central figure of the movement, Tarsila do Amaral elevated the Afro-Brazilian figure into a monumental subject in her work A Negra (1923), restoring a dignity long denied and affirming its essential role in the cultural construction of Brazil, in rupture with colonial representations.

Maria Martins, in turn, integrated Amazonian myths into the language of Surrealism, which she diverted from its European matrix (Breton, Bataille) to transform it into a tool of cultural affirmation. The organic forms of her sculpture Canto do mar (1952) translate the vital impulse of ancestral myths and approach the “thirst for voice” described by Nietzsche, giving materiality to the invisible. In doing so, Maria Martins projected into the modern imaginary a living Brazilian memory, where the voices of repressed traditions metamorphose into a universal symbol.

This approach recalls the extent to which memory is articulated in a dynamic navigation between past, present, and future. Thus, the vestiges of the past are reread in light of a lived and interpreted present, opening new perspectives for the future. It is in this sense that Glauco Rodrigues’s work Pau-Brasil, 1974 denounces the ambivalence of the founding symbol of the nation: at once an emblem of national pride and, in counterpoint, a reminder of a system of colonial exploitation. By adopting a pop and ironic aesthetic, the artist highlights the persistence of hierarchies inherited from colonization and questions the ideological construction of Brazilian identity.

This identity remains, moreover, deeply fractured by the incomplete integration of Afro-descendant memory. Nádia Taquary’s masks, mobilizing the aesthetic and spiritual codes of the Orixás as well as the narratives of enslaved Black women, connect the present to erased memories. Her works function as a true counter-archive, engaging a process of symbolic reparation. Likewise, the contemporary use of joias de crioula transforms objects once stigmatized as marks of slavery or resistance into symbols of pride and collective power.

In recent decades, thanks to powerful curatorial, artistic, and intellectual gestures, the narrative has been gradually reconstructed. The Museum of Black Art, founded by Abdias Nascimento in the 1950s, paved the way by asserting the legitimacy and visibility of Afro-Brazilian creation, breaking with centuries of invisibilization. In parallel, Darcy Ribeiro founded in 1953 the Museum of the Indian, the first Brazilian institution explicitly dedicated to Indigenous cultures, while Lina Bo Bardi, in the 1950s and 1960s, boldly integrated Afro-Brazilian and Indigenous objects into her exhibitions (Bahia no Ibirapuera, A Mão do Povo Brasileiro), blurring the boundaries between art, craft, and popular culture and inscribing these productions into the museum field. In the same perspective, Emanoel Araújo’s seminal project A Mão Afro-Brasileira consolidated this movement by cataloguing Afro-Brazilian artists, especially Baroque masters whose ethnic origins had been concealed, thereby reactivating the central role of their contributions to Brazilian art history. Continuing and updating these pioneering initiatives, the exhibition Um defeito de cor (Museum of Art of Rio, curated by Marcelo Campos, 2025) reinscribes Afro-Brazilian memory into the present, articulating the legacies of slavery and structural racism with the languages of contemporary art.

The introduction of Afro-descendant and Indigenous artists into collections, publications, and exhibitions constitutes a fundamental turning point. Yet such visibility cannot be limited to musealization: it must be accompanied by real recognition and respect for their traditions, as well as the demarcation of their territories—otherwise it risks becoming a new form of instrumentalization. The growing commodification of Indigenous art illustrates this dynamic, perpetuating within an art market still traversed by colonial logics a system that remains the antithesis of equality. In counterpoint, the Makhu do not limit themselves to producing works for the market: with the initiative Selling Paintings to Buy Land, they redirect the revenues from their art toward the repurchase of ancestral lands, transforming artistic practice into an instrument of historical reparation and sovereignty.

In the same critical perspective, Denilson Baniwa rereads the Anthropophagic Manifesto by emphasizing that the modernist appropriation of the Indigenous figure reproduced a dynamic of dispossession in which the Indigenous remained an aesthetic symbol yet was deprived of political voice. His proposal of an inverted anthropophagy shifts the paradigm: it is no longer the modernist elites who devour the Indigenous as a mere cultural metaphor, but Indigenous artists who assert their power by digesting, diverting, and subverting institutions, narratives, and codes of contemporary art. This inversion paves the way for a true symbolic decolonization, in which Indigenous peoples are not merely raw material for modernity but producers of worlds and knowledges.

These issues resonate in current exhibitions that shift the center of gravity of the museological debate. In Brazil, InsurgĂŞncias IndĂgenas (SESC Rio, 2025) highlights the aesthetic and political potency of contemporary Indigenous creation, explicitly linking it to territorial struggles and sovereignty. In Europe, Le Chant des ForĂŞts (The Song of the Forests, Quai Branly, 2025) mobilizes narratives and practices from Amazonian communities but also raises the question of the place of Indigenous cosmologies in an institution still marked by colonial heritage. Finally, the project The YĂŁna and the Museums (British Museum/British Council, 2025) testifies to the ways Western institutions seek dialogue with Indigenous communities, while also revealing the limits of a framework in which the restitution of voices remains partial. These initiatives show that the decolonization of museums cannot be reduced to symbolic inclusion: it requires a profound transformation of institutional logics in order to recognize Indigenous peoples as epistemic actors and creators of knowledge in their fullness.

It is within this tension, between openness and the persistence of asymmetries, that the question of Brazilian memory is inscribed. It remains marked by the fractures of a system built upon slavery and colonization, long concealed yet still structuring, where incomplete integration at the local level merely reflects enduring domination on a global scale. One may indeed question the scant accessibility and rare representation of Brazilian art in Europe until recently, as well as the belated recognition of its artists, often legitimized in Brazil only after being co-opted and valued by the international market. Behind the celebration of diversity, hegemonic logics persist. Yet it is precisely within these fissures that artworks trace their counterpoint: by disarming dominant narratives, they open breaches, reinscribe erased memories, and sketch the possibility of a memory of the future, not as an instrument of domination, but as a space of struggle and liberation.

We invite you to explore the journal of the exhibition Cosmogonias Brasileiras and immerse yourself in the reflections, images, and voices that shape this plural universe. Featuring notably texts by curator and anthropologist HĂ©lio Menezes, co-curator of the 35th SĂŁo Paulo Biennial, former Artistic Director of Museu Afro Brasil, recognized by ArtReview in 2021 as one of the 100 most influential figures in contemporary art.

Click on the whatsaap button on the right to connect with us and receive the preview of the exhibition.