Yet the very title of this Biennale is drawn from another poem, “Nem todo viandante anda estradas – Da humanidade como prática” ( Not All Travellers Walk Roads — Of Humanity as Practice), is drawn from another poem, Da calma e do silêncio (Of Calm and Silence), written in 1990 by Afro-Brazilian author Conceição Evaristo and published in Cadernos Negros, the landmark São Paulo series dedicated to African diasporic literature long excluded from Brazil’s mainstream publishing.

It is within this turbulence that the research period of the five curators, led by Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung (Cameroon-born, based in Berlin, and director of the Haus der Kulturen der Welt) unfolded during what he calls an alarming “acceleration of the dehumanization project,” marked by wars, famines, and starvation across inumerous conflict zones from Anafis to Bamenda, Gaza to Coma, Kashmir to Khartoum, Mariupol to Nepidao, Jamina to Tigray, Port-au-Prince to Veracruz.

Against the deceptive notion that “we need war to make peace,” the curators team highlight how a specific kind of occupant systematically destroys its host. Yet, humanistic investigation aligned with non-hegemonic thought, engaged with aesthetics, can still play an intuitive role in reshaping our many interconnected and crisis-ridden worlds.

We know that estuaries are coastal environments shaped by the tides, where fresh water flowing from rivers meets the salt water of the sea, spaces of constant transformation. An aquatic environment and the ocean, distinct bodies of water, yet capable of stirring the same space and giving rise to life. From this image, the estuary becomes a curatorial metaphor, a temporary figure that shaped the architecture of the 36th Bienal de São Paulo.

The exhibition design engages the idea of migratory flows and the estuary’s shifting waters, proposing a circulation that reinforces this sensibility: the curtains introduce movement and permeability, recalling the fluid rhythms of water. Their presence softens the monumental scale of the pavilion, creating intimate passages an a welcoming atmosphere, where visitors can drift and pause. The vision deliberately avoids relying solely on dominant narratives, instead opening space for unconscious dimensions that take shape in a verticality resisting linearity. These vertical installations interrupt the usual trajectory through the pavilion, encouraging not one but many readings historical, critical, and experiential. In turn, this verticality fosters a heightened awareness of displacement and coexistence.

Guided by the estuary as both metaphor and method, the Bienal unfolds through three curatorial themes, each developed in two chapters that explore poetry and memory. The first, inspired by Conceição Evaristo, proposes slowing down and listening to the subtleties of nature, opening up worlds submerged by poetry. The second, based on René Depestre, invites us to reflect on the other, crossing social boundaries and suggesting forms of collective coexistence. The third takes the estuary as a metaphor for convergence, revisiting the impact of coloniality and evoking references such as Manguebeat, Patrick Chamoiseau, and Édouard Glissant. Together, these fragments transform the Biennial into a space of care, resistance, and imagination of shared futures.

Chapter 1 – Frequencies of Landings and Belongings

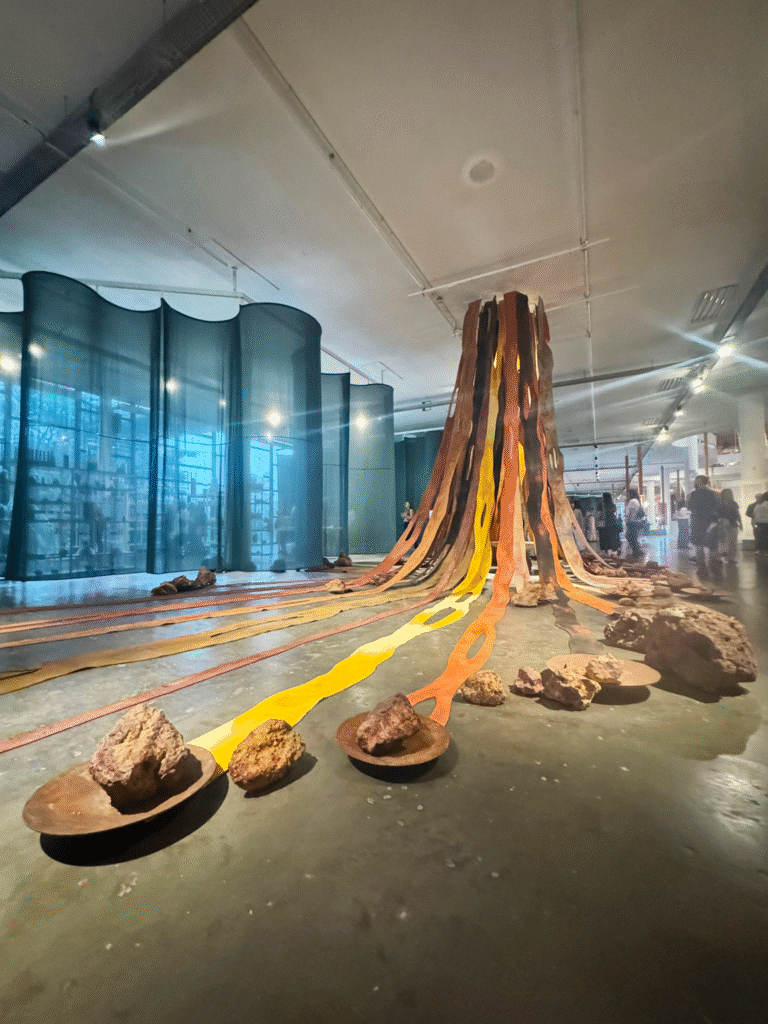

Under the scent of wet earth and the murmur of flowing water, this chapter unfolds, drawing us back to the soil, to the land’s potential and the vibration that sustains life. Here, the garden installation by Precious Okoyomon transforms the Pavilion with organic materials in constant flux, creating an immersive environment where visitors can walk through the space in a meditative, almost Zen-like experience.

In the intimate geography of impossible encounters, in the fragile balance of elements that never fully surrender, emerges Nádia Taquary‘s bronze installation Ìrókó‘s draws on Afro-Brazilian spiritual traditions, where the cosmic tree embodies ancestry, vitality, and continuity between worlds. Through the presence of Ìyámis sculptures, the work materializes the mythical tree through which the orixás descended to Earth. Combining organic materials, symbolic forms, and references to Candomblé, Cosmic Tree reflects on the resilience of Black identity and the sacred connection between earth and cosmos.

Carla Gueye’s Cabinet of Invisible Desires, 2025 draws on Wolof seduction rituals and vernacular knowledge into sculptures, paintings and videos turning intimacy into a poetic and political space of relation.

This collective spirit manifests in Sertão Negro, whose work revolves around two stone circles borrowed from the Guarani of Jaraguá, symbolizing respect for the earth’s time alongside two walls that exhibit, respectively, the project’s history and ongoing activities. From these foundational territories, new geographies of resistance begin to smolder.

Chapter 2 – Grammars of Defiance

This chapter ignites another kind of geography one of resistance. Here, “the small rebellious flame fighting death,” as curator Alya Sebti recalls, becomes a lighthouse guiding insurgent navigations through overturned colonial archives. Through diverse artistic practices, this chapter weaves together acts of cultural reclamation and healing: Suchitra Mattai transforms ancestral embroidery into rituals honoring Indo-Caribbean women’s silent revolutions, creating spaces where alternative cosmogonies challenge Western narratives;

While Ruth Ige makes time itself a medium of coexistence through immersive portals where hooded figures crafted with baobab dust, indigo, and Brazilian clays invite viewers into cyclical temporalities where ancestors and future beings dance together. These works embody a poetics of defiance, where colonized bodies reclaim their voices, creating artistic trampolines to live, grow, and soar at the edge of the abyss. From these flames of insurgence, movement itself becomes the next grammar of survival.

Other installations reveal situations just as dire, sometimes even more striking. Among them, Forensic Architecture/Forensis presents The People’s Court I, 2025, a multi-year investigation into the transatlantic petro-extractivist complex. Using advanced digital reconstructions, the work shows how oil exploitation in the Niger Delta erases homes, unsettles geology, and devastates communities. The artists transforms forensic evidence into a collective forum, making the environmental and human costs of extractivism impossible to ignore.

Chapter 3 – On Spatial Rhythms and Narratives

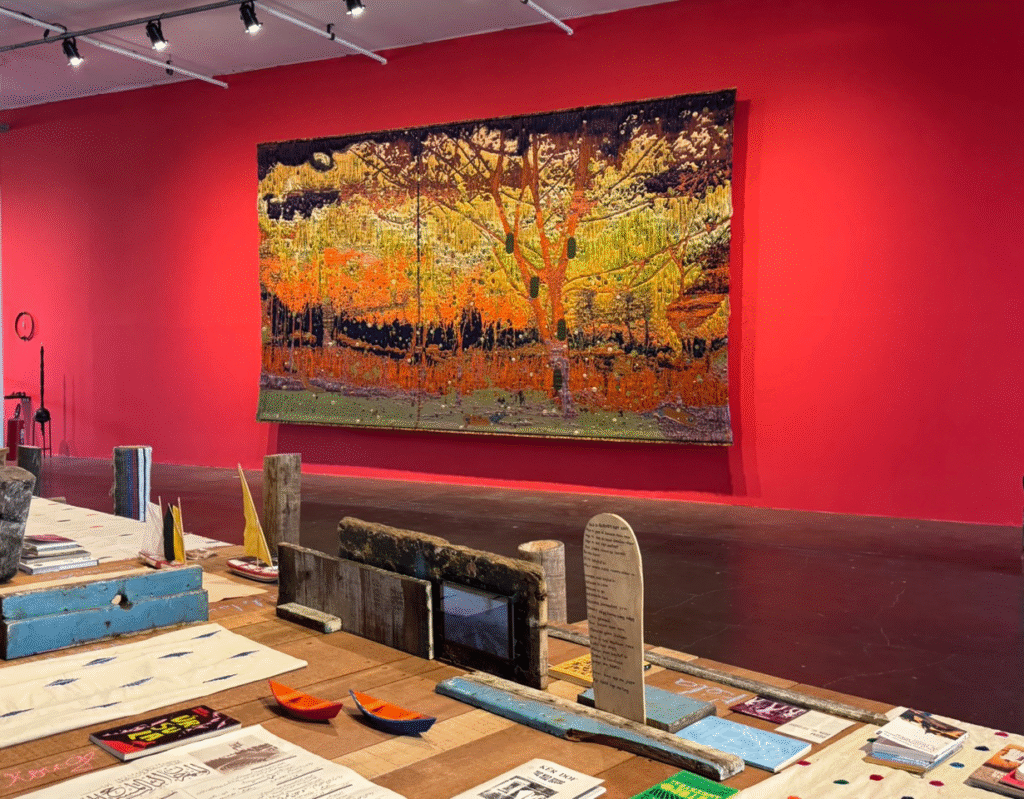

From insurgent flames emerge the spatial rhythms of Chapter 3, where resistance becomes movement and movement becomes narrative. Through works that transform spaces of passage into sites of memory and resistance, artists create intimate geographies of uprootedness: Museu das Terras Brasileiras is part of Marlene Almeida’s broader project Encyclopedia of the Lands of the World, a poetic and critical archive built from earth pigments, stones, fragments of history, cartography, and oral memory to reimagine territories and belonging.

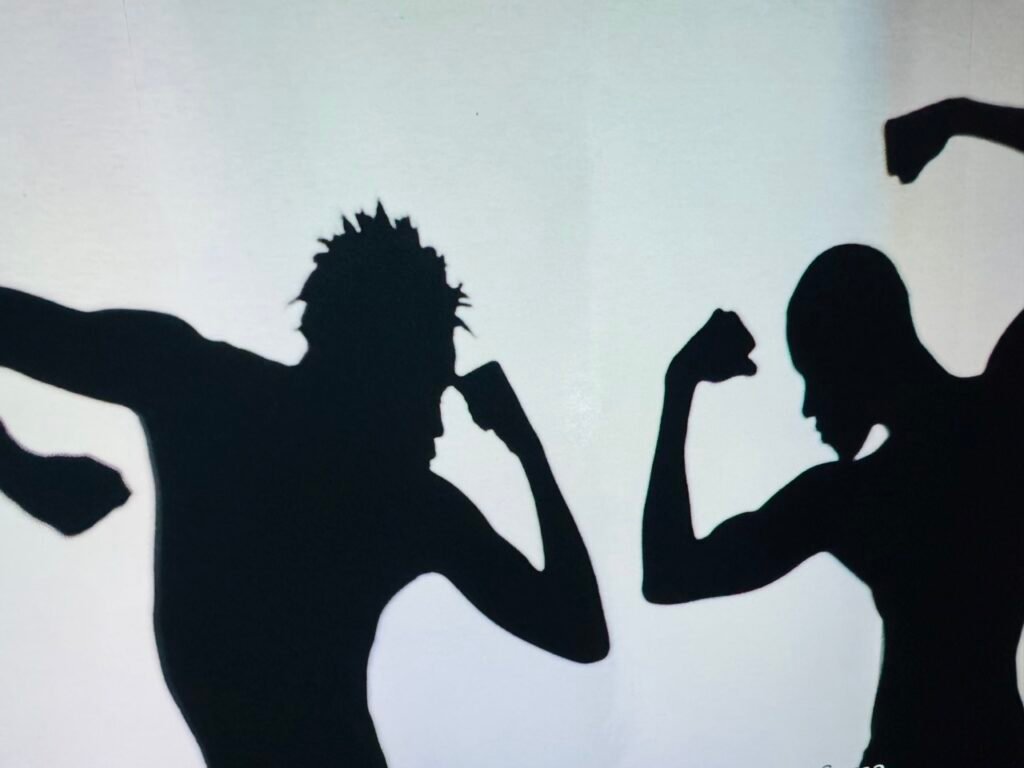

If Almeida roots her work in the soil as archive and living body, Márcia Falcão turns to the body itself as territory. Her Ginga from Capoeira em Paleta Alta, 2024 uses thick layers of oil, charcoal, and pastel to fragment bodies in liminal states, challenging normative structures through corporeal forms that dissolve into masses. These works reveal how bodies carry their territories even when displaced, mapping narratives where each step represents both loss and discovery, each border crossed becomes a small death and rebirth, and each gesture embodies a resistance rhythm that refuses containment.

Chapter 4 – Care Flows and Plural Cosmologies

In Chapter 4, ancestral practices that break away from colonial and patriarchal models of knowledge rise to the surface. Here, care becomes current and current becomes cosmology, as waters connecting distant shores carry the memory of bodies forced across oceans and the wisdom born of these crossings now flows as healing practice. Collaborative interactions between species and their environments form vital tissues of survival, not only for individual organisms but for entire ecologies.

Through transformative works, artists translate these currents: Gervane de Paula’s installation transforms personal and collective memory into a living archive of resistance, rooted in his experience growing up in Mato Grosso during Brazil’s military dictatorship. His universe is populated by sculptures of animals typical of Brazil, where the bestiary of the land intertwines with local folklore to evoke both myth and daily life. In this fusion, his art becomes at once poetic and political, reclaiming silenced histories while reimagining belonging through forms deeply tied to the territory. From these rooted memories, the Bienal expands outward into Brazil’s diverse cultural landscapes, where ancestral knowledge, popular traditions, and revolutionary gestures offer other ways of conjugating humanity.

Bonaventure share how traveling through Brazil reveals not a single narrative, but a spectrum of humanities and way of being. They surface in the rhythms of maracatu masters, in the legends of Mangabeira around Nasaozubi and Mundo Livre, and in the histories of the Dragão do Mar, Francisco José do Nascimento, whose leadership of the Jangadeiros in Fortaleza brought about the abolition of slavery in Ceará in 1884, four years before the rest of Brazil. They echo in the Egungun festival and the oriki poetry of Itaparica in Bahia, honoring the orixás. These currents of tradition and resistance set the stage for connections that reach across the Atlantic, where echoes of Brazil’s histories meet those of Africa.

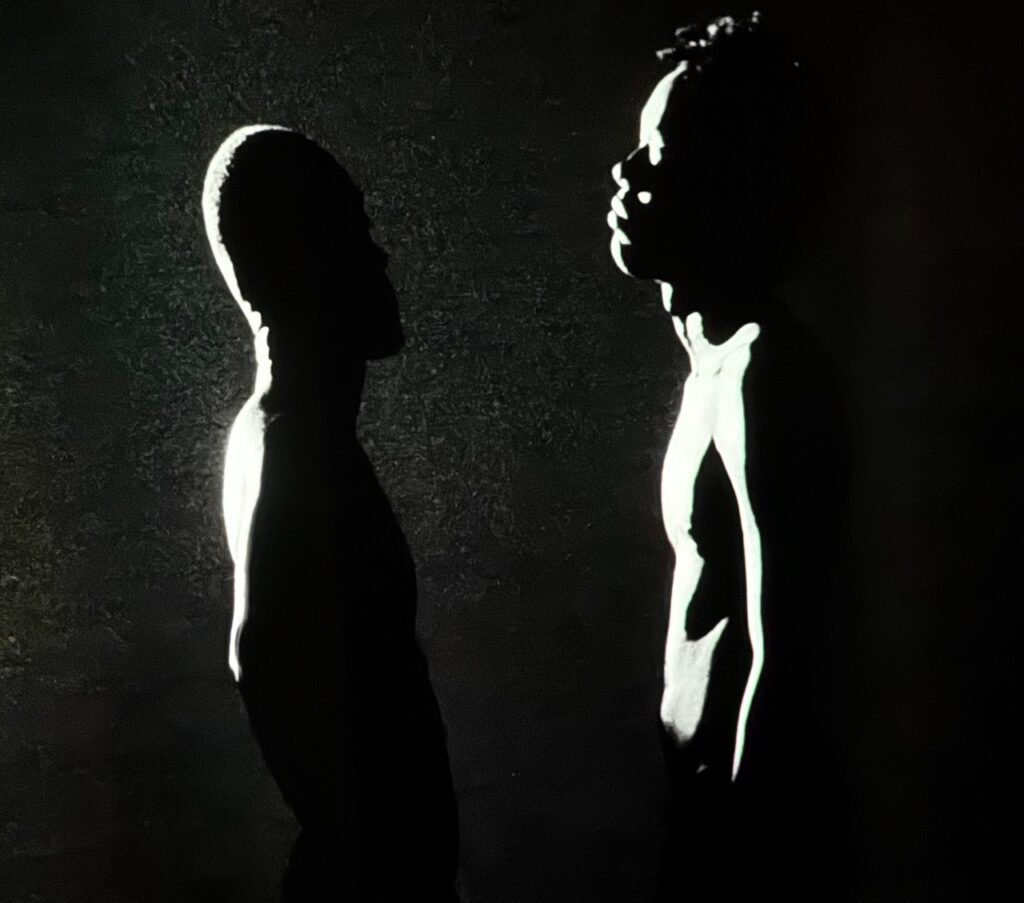

In Helena Uambembe’s Tale, Long Long Long Ago, the narrative begins at the dawn of the earth’s formation, when two brothers emerged from the same soil as embodiments of creation itself. Their bond, once unbreakable, fractured into conflict, tearing the land apart and casting Africa and Brazil to opposite sides of the ocean. In the artist’s vision, this primordial rift is at once a wound and a bridge, a site where memory and rhythm continue to reverberate across the waters, binding the continents through echoes of loss and connection.

This resonance carries into Hamedine Kane’s The Belly of the Atlantic, where embroidered textiles, everyday objects, fragments of fishing nets, and videos evoke the traces of ocean crossings. By turning humble materials into a poetic and political archive, Kane transforms the debris of passage into testimony keeping alive the voices of those whose journeys were marked by displacement and survival.

Chapter 5 – Cadences of Transformation

From the currents of care emerge the transformation, where change reveals itself not as rupture, but as the creative breath of life itself. Here, kinetic works pulse in constant flux, from Antonio Társis suspends vast curtains woven from thousands of used matchboxes, transforming discarded fragments into monumental tapestries. The work evokes both danger and survival: fire as destruction, but also as warmth and resistance, echoing the precarious conditions of life in Brazilian favelas where such objects circulate. By elevating these fragile materials into immersive environments, Társis reclaims what is overlooked, turning memory and marginality into a powerful collective testimony.

María Magdalena Campos-Pons creates floating fabric installations that weave together Afro-Cuban spirituality and histories of migration. At the heart of the work lies a plant, like a rediscovered treasure, reached through a labyrinthine path that unfolds as a poetic journey, allowing us both to see outward and to be seen, as if within a ritual space. Here, the body becomes a vessel of storytelling, where identity emerges as fragment and continuum, and personal memory expands into a collective cartography of displacement, resilience, and cultural survival

In The Nest of the Eternal Present, from Michele Cacciofera, the sculpted birds and eggs evoke cycles of birth and metamorphosis, suggesting that transformation is both a natural and a spiritual condition. His practice speaks through organic materials, affirming art as a living process where matter and imagination are continually reborn.

These installations reinterpret cultural traditions as evolving organisms, transforming over the four months of the exhibition and inviting the audience to witness living processes that mirror our own mutable condition. They ask how we conjugate our humanity with ourselves and others, showing transformation not as a destination but as a method, a dance between past, present, and becoming. Each return is a meeting with a different Biennial, like waters that are never the same. In this ceaseless metamorphosis, beauty emerges as the final act of resistance.

Chapter 6 – The Untreatable Beauty of the World

Closing the chapter 6 completes the exhibition’s circle, revealing beauty as the ultimate act of resistance against all projects of dehumanization. Yes, there is beauty in the world and in the combination of humans.

This reflection extends to a dedication to Madame Koyo Kouoh, a renowned curator and cultural leader who embodies beauty inside and out, and whose lifelong commitment has amplified African and diasporic voices across the global art world. Her legacy resonates with the curatorial theme of the Historical Room, which places emphasis on Afro-descendant creators alongside Asian and Arab voices.

Brazilian artists featured in this section include Heitor dos Prazeres, Maria Auxiliadora, Maxwell Alexander, and Edival Ramosa. At its center stands a tribute to Sir Frank Bowling, whose monumental abstract paintings engage with diaspora and memory, establishing a dialogue at once global and ancestral. In 2005, Bowling became the first Black artist to be elected to the Royal Academy of Arts, a landmark moment in art history that continues to echo within this room.

Edival Ramosa’s geometric vision, rooted in circular and totemic forms, positions him as a singular and indispensable figure within Brazil’s tradition of experimental geometric abstraction. It was during his years in Milan in the 1960s and 1970s that his artistic poetics fully took shape. Spheres, columns, cocoons, moons, comets, arrows, and other “object-forms” populate his formal vocabulary, at once evoking ancestral forces and universal signs. It is no coincidence that when we encounter his work today, it often feels both familiar and elusive echoing the collective memory of Afro-Brazilian art, as if his language had long been inscribed within it.

Mohamed Melehi (1936–2020) holds a fundamental place in the history of postcolonial Moroccan art and in the modernism of the Global South. His trajectory spans the experience of abstraction in Rome and New York during the 1960s to the full maturation of the wave motif, his visual signature. A spirit of aesthetic revolution and of post-independence Moroccan affirmation, his work bridges the Mediterranean and the Atlantic in a cosmopolitan path that transcends borders and asserts itself as a universal language.

By bringing Ramosa and Melehi together, we see how two experiences of origin, one rooted in Brazil and the other in North Africa, unfold in dialogues with Europe and the United States, but always return to the Atlantic as a meeting point. Both create an abstract and symbolic lexicon that, born of different contexts, converges in the same universal language: one that connects territories, memories, and identities through form, rhythm, and the spirituality of matter.

Madame Zo’s work further expands this horizon by taking Madagascar as its starting point, where she is recognized for her textile creations at the border between art and craft. Drawing inspiration from traditional Malagasy techniques and patterns, she has developed a singular abstract vocabulary, deeply shaped by the environmental and sociopolitical issues of Madagascar. Woven with copper threads, herbs, wood, plastic, food scraps, and magnetic tapes, her works transform everyday materials into visual commentaries on contemporary urgencies. Copper, a recurring element, can be read both as a reference to communication technologies and to healing, for its capacity to conduct energy, what Bonaventure has described as “techno-spiritual” materials. Meanwhile, the use of herbs points to alternative therapeutic practices, while the newspaper cutouts incorporated into the pieces evoke the circulation and contestation of information.

A Brazilian Bienal that did not acknowledge the works of Japanese artists the country’s first immigrant community would be incomplete. It is in this context that the installation of Gōzō Yoshimasu is presented.

Experimenting with words, typography, and punctuation, while incorporating fragments of foreign languages and found texts, Yoshimasu’s poems celebrate the unruly multiplicity of language. His manuscripts unfold as visual and textual collages, enriched by literary references and idioms gathered through travel and correspondence. Much of this work is dedicated to transcriptions of postwar poet and thinker Takaaki Yoshimoto, Yoshimasu’s mentor who passed away in 2012. In these transcriptions, Yoshimasu embraces what he calls the “poetic obligation” of a survivor recalling the devotional act of copying Buddhist sutras while simultaneously renewing and translating the original text.

The 36th Bienal de São Paulo brings together 125 artists, including 6 collectives, offering a panorama where plurality emerges both through individual trajectories and collaborative practices. Of these, there are 50 men and 69 women, reflecting a slight female majority (55%). Notably, Black representation is significant: 32 Black men (26% of the total) and 30 Black women (24%), alongside 4 Indigenous artists.

While the Bienal itself avoids classifications by nationality, the curator stresses that the selection was guided instead by a migratory and non-statist approach, it is telling that the geographic mapping echoes this diversity: a predominance of artists from Latin America and the Caribbean (25%), Africa (20%), and North America (20%), complemented by voices from Europe, Asia, and Oceania. This distribution creates a vivid mirror of Brazilian society, where Afro-descendant, Indigenous, migrant, and diasporic trajectories converge, situating the Bienal within a dynamic of plurality and global resonance.

Ultimately, the Bienal extends an invitation to see ourselves as part of a larger choreography of existence. Despite differences in origin and circumstance, we carry shared archives of memory and collective unconscious. Like the sweeping flights of birds or the synchronized currents of fish, humanity too moves as a single, interconnected force an energetic migration that transcends borders and reminds us that we are, at our core, one.

The Artists

Adama Delphine Fawundu, b. 1971 – Sierra Leone: Hesse Flatow

Adjani Okpu-Egbe, b. 1979 – Cameroon: Sulger-Buel Gallery

Aislan Pankararu, b. 1985 – Brazil 🇧🇷

Akinbode Akinbiyi, b. 1946 – Nigeria

Alain Padeau, b. 1956 – France

Alberto Pitta, b. 1959 – Brazil 🇧🇷: Nara Roesler

Aline Baiana, b. 1985 – Brazil 🇧🇷

Amina Agueznay, b. 1963 – Morocco: Loft Art Gallery

Ana Raylander Mártis dos Anjos, b. 1981 – Brazil 🇧🇷

Andrew Roberts, b. 1995 – Mexico: Pequod Co.

Antonio Társis, b. 1995 – Brazil 🇧🇷: Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel

Behjat Sadr, 1924–1995 – Iran: Dastan Gallery

Berenice Olmedo, b. 1987 – Mexico: Jan Kaps

Bertina Lopes, 1924–2012 – Mozambique: Richard Saltoun Gallery

Camille Turner, b. 1960 – Canada

Carla Gueye, b. 1980s – Senegal

Cevdet Erek, b. 1974 – Turkey: AKINCI

Chaïbia Talal, 1929–2004 – Morocco

Christopher Cozier, b. 1959 – Trinidad & Tobago: David Krut Projects

Cici Wu, b. 1989 – Hong Kong: 47 Canal

Yuan Yuan, b. 1989 – China: Kiang Malingue

Cynthia Hawkins, b. 1950 – USA: Paula Cooper Gallery

Edival Ramosa, b. 1947 – Brazil 🇧🇷

Emeka Ogboh, b. 1977 – Nigeria: Imane Farès

Ernest Cole, 1940–1990 – South Africa: Goodman Gallery

Ernest Mancoba, 1904–2002 – South Africa: Galerie Mikael Andersen

Farid Belkahia, 1934–2014 – Morocco: Loft Art Gallery

Firelei Báez, b. 1981 – Dominican Republic: Hauser & Wirth

Forensic Architecture / Forensis, founded in 2010 – UK

Forugh Farrokhzad, 1935–1967 – Iran

Frank Bowling, b. 1936 – Guyana/UK: Hauser & Wirth

Frankétienne, 1936–2024 – Haiti

Gê Viana, b. 1986 – Brazil 🇧🇷: Galeria Superfície

Gervane de Paula, b. 1962 – Brazil 🇧🇷: Cerrado Galeria

Gōzō Yoshimasu, b. 1939 – Japan: Take Ninagawa

Hao Jingban, b. 1985 – China: Blindspot Gallery

Hajra Waheed, b. 1980 – Canada: mor charpentier

Hamedine Kane, b. 1983 – Senegal/Mauritania: ElaineAlain

Hamid Zénati, 1944–2022 – Algeria

Heitor dos Prazeres, 1898–1966 – Brazil 🇧🇷: Almeida & Dale

Helena Uambembe, b. 1994 – South Africa/Angola: Goodman Gallery

Hessie, 1936–2017 – Cuba/France: Galerie Arnaud Lefebvre

Huguette Caland, 1931–2019 – Lebanon: Mennour

Imran Mir, 1950–2014 – Pakistan: Canvas Gallery

Isa Genzken, b. 1948 – Germany: David Zwirner

Joar Nango (Girjegumpi), b. 1979 – Norway/Sápmi

Josèfa Ntjam, b. 1992 – France/Cameroon: Galerie Christophe Gaillard

Juliana dos Santos, b. 1987 – Brazil 🇧🇷

Julianknxx, b. 1980s – Sierra Leone/UK: White Cube

Kader Attia, b. 1970 – France/Algeria: Lehmann Maupin

Kamala Ibrahim Ishag, 1939–2022 – Sudan: Circle Art Gallery

Kenzi Shiokava, 1938–2021 – Japan/Brazil 🇧🇷: Nicelle Beauchene

Korakrit Arunanondchai, b. 1986 – Thailand: Clearing

Leiko Ikemura, b. 1951 – Japan: Galerie Karsten Greve

Laila Hida, b. 1983 – Morocco

Laure Prouvost, b. 1978 – France: Lisson Gallery

Leila Alaoui, 1982–2016 – Morocco: Galleria Continua

Leo Asemota, b. 1967 – Nigeria

Leonel Vásquez, b. 1979 – Colombia: Instituto de Visión

Lidia Lisbôa, b. 1970 – Brazil 🇧🇷: Almeida & Dale

Lynn Hershman Leeson, b. 1941 – USA: Bridget Donahue

Madame Zo, 1956–2020 – Malagasy

Madiha Umar, 1908–2005 – Iraq

Malika Agueznay, 1938–2019 – Morocco: Loft Art Gallery

Manauara Clandestina, b. 1990s – Brazil 🇧🇷:

Mansour Ciss Kanakassy, 1957–2021 – Senegal

Mao Ishikawa, b. 1953 – Japan: Taka Ishii Gallery

Márcia Falcão, b. 1990 – Brazil 🇧🇷: Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel

Maria Auxiliadora, 1935–1974 – Brazil 🇧🇷: Galeria Estação

María Magdalena Campos-Pons, b. 1959 – Cuba/USA: Alexander Gray Associates

Marlene Almeida, b. 1950s – Brazil 🇧🇷: Almeida & Dale

Maxwell Alexandre, b. 1990 – Brazil 🇧🇷: David Zwirner

Meriem Bennani, b. 1988 – Morocco: Clearing

Metta Pracrutti, founded in 2025 – India

Michele Ciacciofera, b. 1969 – Italy: Galerie Michel Rein

Ming Smith, b. 1950 – USA: Pippy Houldsworth Gallery

Minia Biabiany, b. 1988 – Guadeloupe: Crèvecœur

Moffat Takadiwa, b. 1983 – Zimbabwe: Nicodim Gallery

Mohamed Melehi, 1936–2020 – Morocco: Loft Art Gallery

Moisés Patrício, b. 1984 – Brazil 🇧🇷: Mendes Wood DM

I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih (Murni), 1966–2006 – Indonesia

Myriam Omar Awadi, b. 1982 – Réunion (France): Selma Feriani Gallery

Myrlande Constant, b. 1968 – Haiti: Rele Gallery

Nádia Taquary, b. 1973 – Brazil 🇧🇷: Paulo Darzé Galeria

Nari Ward, b. 1963 – Jamaica/USA: Lehmann Maupin

Nguyễn Trinh Thi, b. 1973 – Vietnam

Noor Abed, b. 1988 – Palestine

Nzante Spee, 1953–2005 – Cameroon

Olivier Marboeuf, b. 1960s – France/Guadeloupe

Olu Oguibe, b. 1964 – Nigeria/USA: James Cohan

Oscar Murillo, b. 1986 – Colombia: David Zwirner

Otobong Nkanga, b. 1974 – Nigeria/Belgium: Lumen Travo

Pélagie Gbaguidi, b. 1965 – Benin: Galerie Maïa Muller

Pol Taburet, b. 1997 – France: Balice Hertling

Precious Okoyomon, b. 1993 – Nigeria/USA: Regen Projects

Raukura Turei, b. 1982 – New Zealand: Bergman Gallery

Raven Chacon, b. 1977 – USA (Navajo)

Iggor Cavalera, b. 1970 – Brazil 🇧🇷

Laima Leyton, b. 1980 – Brazil 🇧🇷

Etenhiritipa Xavante Community, founded in 2007 – Brazil 🇧🇷

Rebeca Carapiá, b. 1993 – Brazil 🇧🇷: Galeria HOA

Richianny Ratovo, b. 1990s – Madagascar

Ruth Ige, b. 1994 – Nigeria/New Zealand: Page Galleries

Sadikou Oukpedjo, b. 1970 – Togo: Galerie Cécile Fakhoury

Sallisa Rosa, b. 1986 – Brazil 🇧🇷: A Gentil Carioca

Sara Sejin Chang (Sara van der Heide), b. 1977 – South Korea/Netherlands

Sérgio Soarez, b. 1960s – Brazil 🇧🇷

Sertão Negro, founded in 1990 – Brazil 🇧🇷

Sharon Hayes, b. 1970 – USA: Tanya Leighton

Shuvinai Ashoona, b. 1961 – Canada (Inuit): Feheley Fine Arts

Simnikiwe Buhlungu, b. 1995 – South Africa: Blank Projects

Song Dong, b. 1966 – China: Pace Gallery

Suchitra Mattai, b. 1973 – Guyana/USA: Kavi Gupta

Tanka Fonta, b. 1960s – Nigeria

Thania Petersen, b. 1980 – South Africa: WHATIFTHEWORLD

Theo Eshetu, b. 1958 – Ethiopia/Italy: Tiwani Contemporary

Théodore Diouf, b. 1990s – Senegal

Theresah Ankomah, b. 1989 – Ghana: Efie Gallery

Trương Công Tùng, b. 1986 – Vietnam: Galerie Quynh

Tuấn Andrew Nguyễn, b. 1976 – Vietnam/USA: James Cohan

Vilanismo, fouded in 1990 – Brazil 🇧🇷

Werewere Liking, b. 1950 – Cameroon

Wolfgang Tillmans, b. 1968 – Germany: Galerie Buchholz

Zózimo Bulbul, 1937–2013 – Brazil 🇧🇷