Afro-Atlantic Currents in in Brazilian andFrench Artistic Traditions

Brazil is essentially a land of miscegenation and artistic synthesis. Since its formation, it has alwaysbeen a land of migration, absorbing influences from different parts of the world and transformingthem into something unique. This cultural melting pot has shaped its artistic identity, intertwiningEuropean, African and indigenous traditions.

During Baroque period (17th century to the first decades of the 18th century), artistic production wasstrongly linked to manual labor, and Brazilian artists were mostly of African descent or mixed race. Asthe colony’s white population was numerically smaller and focused on administrative and commercialfunctions, artistic crafts were carried out by artisans and sculptors of African origin, many of whomwere enslaved or freed. These artists, often without individual recognition, were responsible forcarving, painting and decorating churches and buildings that marked the Brazilian Baroque aesthetic.

One of the most emblematic examples of this cultural fusion in Brazil is Antônio Francisco Lisboa,known as Aleijadinho. The son of a Black woman and a Portuguese man, Aleijadinho overcame socialprejudice to become a powerful symbol of Afro-descendant contribution to Brazilian art. Hissculptures and architectural works, expressive, dramatic, and profoundly spiritual, reveal howEuropean Baroque forms were transformed through African sensibilities, giving rise to a uniquelyBrazilian Baroque.

Another striking example of this cultural fusion is Mestre Valentim, an Afro-descendant artist active inthe 18th century. Renowned for his talent as a sculptor and urban planner, he was responsible forimportant works in Rio de Janeiro, such as the Passeio Público, Brazil’s first urban park. In this space,he combined elements of European rococo with inventive solutions, adapted to the tropical reality andlocal tastes, reflecting his own artistic sensibility, forged at the intersection of cultures.

Like Aleijadinho, his production reinforces the idea that Brazilian art was born from the confluence ofdiverse influences, being deeply marked by the black contribution, not only in the execution, but also inthe aesthetic and symbolic conception of the works.

In parallel, France’s engagement with Africa during the colonial period, although shaped by distincthistorical dynamics, gave rise to a subtle yet impactful hybridization in the arts. Often overlooked,African influences entered French Baroque through ornamental motifs, material culture, and theincreasing presence of Black figures and aesthetics in court art and decorative traditions.

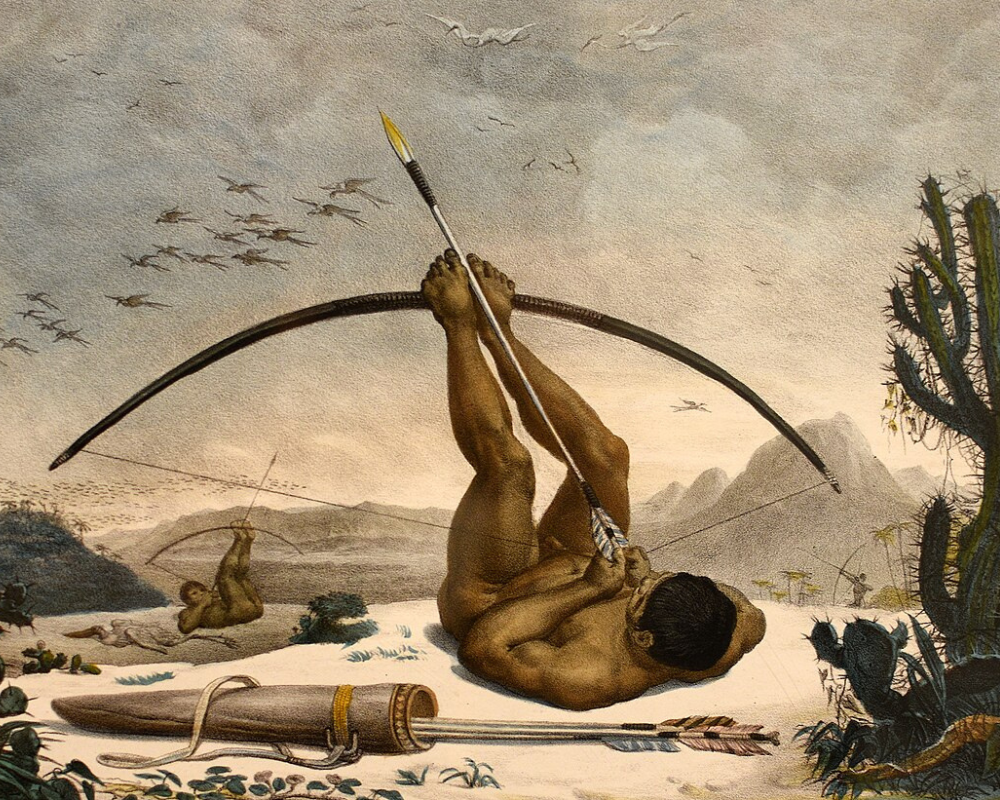

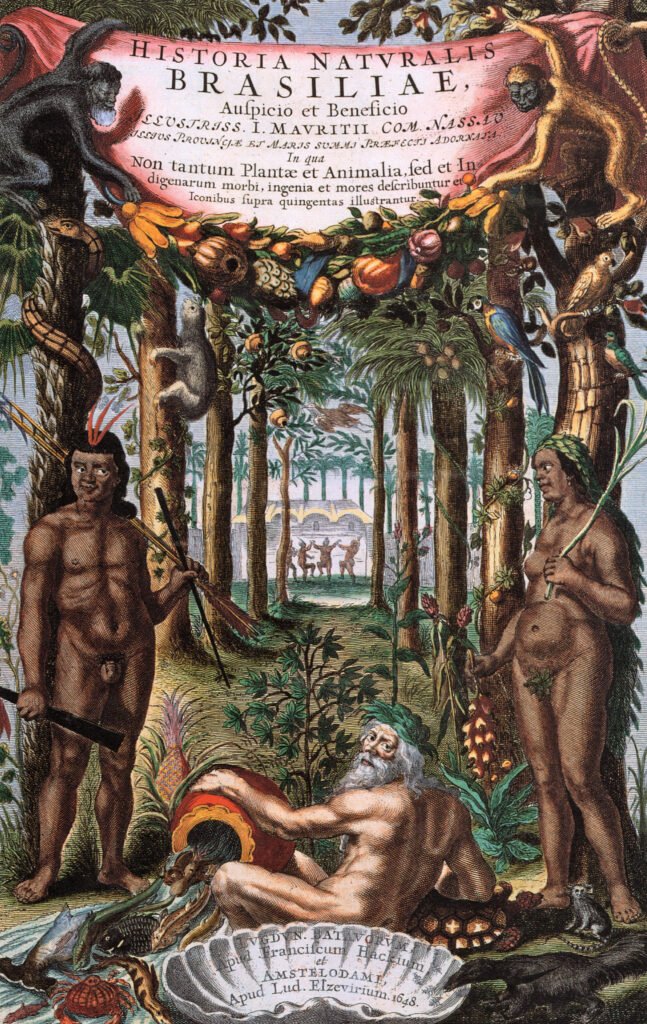

At the Manufacture des Gobelins in Paris, for example, the production of a series of tapestriescommissioned to adorn royal residences reflected a growing fascination with non-European subjectsand styles. More than mere decorative objects, these works captured aspects of the colonial worldand played an active role in constructing an imperial visual language. They became part of the officialiconography of European overseas expansion, subtly reinforcing colonial ideologies.

This cultural entanglement was further amplified by the Catholic conversion of certain Africancolonies and the presence of early French settlements in Brazil during the 16th and 17th centuries.These historical threads created a channel through which exotic imaginaries circulated, eventuallyreaching Brazil, where they intertwined with local anthropological and aesthetic foundations to shapea singular visual language.

The result was a métissage that not only enriched regional artistic traditions but also sowed theseeds for future modernisms, rooted in plurality, resistance, and reinvention.

The French Artistic Mission: Foundations ofAcademic Art in Brazil

The French Artistic Mission: Foundations ofAcademic Art in Brazil

However, the relationship between the two countries goes back centuries, more precisely to March 26,1816, when a group of French artists landed in Rio de Janeiro. Among them, the painters Jean-BaptisteDebret and Nicolas-Antoine Taunay, Johann Moritz Rugendas and Victor Frond under the leadershipof Joachim Lebreton, arrived with the mission of supplying the colony with “good art”.

The invitation came from the Count of Barca, minister to Dom João VI, who was looking to modernizelocal artistic production after the arrival of the Court in Brazil in 1808. Inspired by the French academicmodel and the neoclassical tradition, the French Mission aimed to structure the teaching of the arts inthe country.

Until then, Brazilian art was mostly religious, centered on the decoration of churches and convents.With the arrival of the Royal Family in Rio de Janeiro, there was a demand for portraits, palaceornaments and records of the territory, driving a new cultural phase in line with European standards.

Even before embarking for Brazil, Lebreton gathered a collection of works by European artists,bringing with him a collection of great value. In a country where photography was still non-existent,these paintings played an essential role in recording everyday life, political events and historicalmoments. Thus, the French mission not only formed the basis of academic art education in Brazil, butalso ensured that the events of the time were documented by some of the most renowned Frenchartists.

The group selected by Lebreton played a fundamental role in spreading French neoclassicism andromanticism in Brazil, styles that at the time were associated with sophistication. Ten years after theirarrival, the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts was founded, which became a reference in the training ofBrazilian artists such as Victor Meirelles, Pedro Américo and Eliseu Visconti.

Academic art remained dominant throughout the 18th century until the end of the 19th century, whenthe first outdoor painting movements emerged in France. This new approach paved the way for thefirst European avant-gardes, while in parallel, Brazil witnessed the birth of modern painting, laterconsolidated with the Modern Art Week of 1922.

Modernism, Paris, and the Rise of a BrazilianIdentity

The artistic effervescence of this period was one of the factors that motivated many Brazilian artiststo leave for Paris in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Although France left its mark on Brazilian artthrough its academic teaching, it also contributed to its dissemination in Europe. As early as the 1920s,Brazilian artists such as Alberto da Veiga Guignard, Annita Malfatti, Vicente de Rego Monteiro, VictorBrecheret and Waldemar Cordeiro were exhibiting at the Salons d’Automne and des Indépendants inParis, asserting their presence on the international art scene.

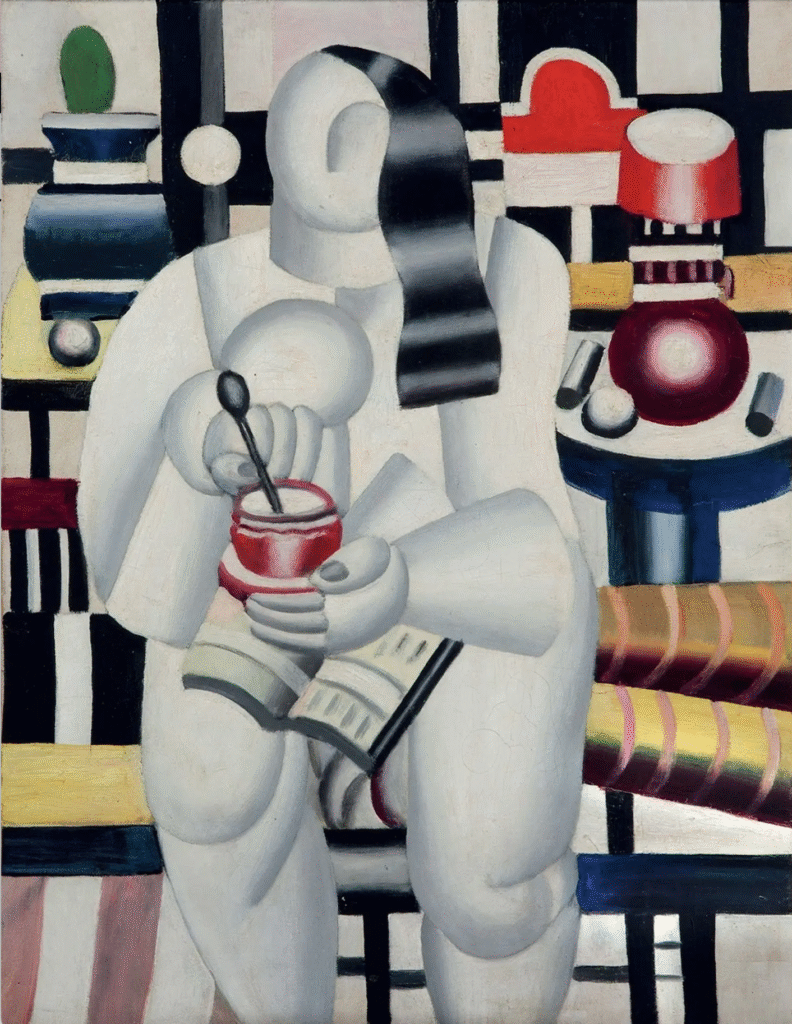

The impact of the French avant-garde on Brazilian modernism is undeniable. After her stay in France,Tarsila do Amaral fused the principles of Cubism and Surrealism with Brazilian references, followingher studies in Fernand Leger’s studio.

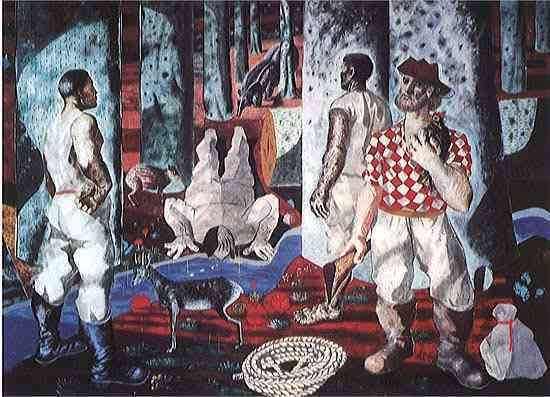

Cândido Portinari is another artist that represents this cultural connection. Although he didn’t live inFrance, his style was influenced by European murals and the French avant-garde. His workincorporates references to European social realism with a unique Brazilian touch.

When they returned to Brazil, these artists brought with them new influences and a strong desire tobreak with traditional academicism. This transformative impulse gained strength after the Modern ArtWeek of 1922, an event that redefined artistic concepts in the country. From then on, Brazilian artisticproduction began to explore new languages, materials and techniques, breaking with establishedtraditions and paving the way for the construction of a modernist identity of its own.

Art Deco Bridges: From Paris to São Paulo

While modernism was gaining momentum in Brazil, the Art Deco movement was consolidating itself inParis, especially with the Exposition Universelle des Arts Décoratifs of 1925. With an aesthetic thatcombined elegance and functionality, its influence spread to various areas, including architecture,interior design, visual arts and painting. In Brazil, Art Deco arrived in the 1920s, initially througharchitecture, and later spread to other artistic expressions.

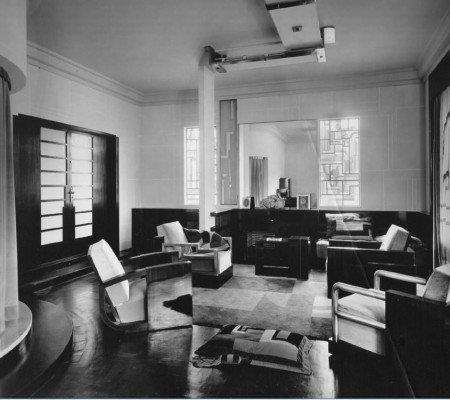

Among the artists who incorporated this aesthetic was John Graz, a Swiss architect and designerwho settled in Brazil from the 1920s onwards. He took part in a number of architectural projects inwhich he incorporated this new trend, as well as making a significant contribution to the developmentof the aesthetic.

An important figure in the consolidation of Art Deco in Brazil was the Italian sculptor Victor Brecheret,one of the founders of the Sociedade Pró-Arte Moderna. His production in the 1930s sums up theinfluence of this movement, especially in sculpture. The Venice Biennale itself recognized this dialoguebetween the Italian diaspora and Art Deco, highlighting his work Virgin and child. This sculptureincorporates minimalist and geometric lines, typical of the movement, while preserving a subtleelegance in the representation of this icon of sacred art.

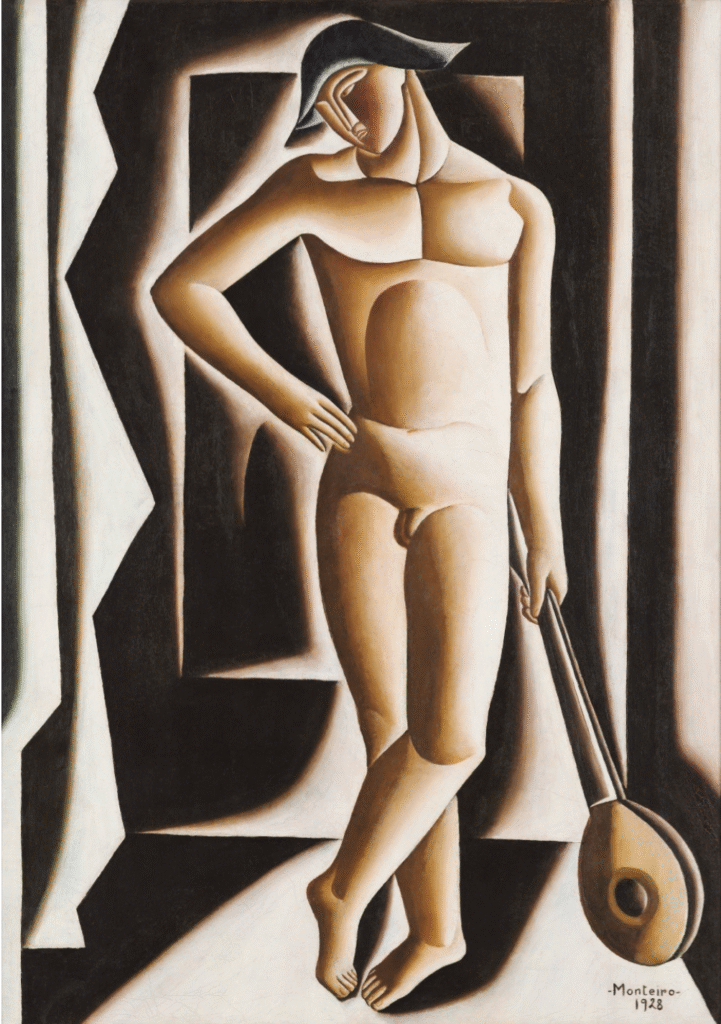

Another influential presence in the consolidation of the Art Deco aesthetic in Brazil was Vicente doRego Monteiro, whose work engaged with the movement from a distinct perspective: theincorporation of elements from Indigenous Brazilian culture.

Rego Monteiro explored the vocabulary of Art Deco with tropical intensity, fusing traces of Marajoaraceramics with the geometric shapes and metallic sparkles of the style. His stylized bodies, bothhuman and animal, oscillate between the ancestral and the futuristic, revealing an original synthesisbetween European avant-garde and indigenous Brazilian tradition.

Thus, Art Deco in Brazil not only absorbed French and Italian influences, but also adapted to the localcontext, becoming an important link between European tradition and emerging Brazilian modernity.

A unique opportunity to explore the relationship between the Art Deco period, its correspondence inBrazil and Brazilian modernity will take place during the ABERTO exhibition at Le Corbusier’s Villa LaRoche in Paris, from May 15 to June 15, 2025. Conceived by Filipe Assis, Claudia Moreira Salles and KikiMazzucchelli, the project establishes dialogues between art and architecture, weaving new narrativesthat connect these historical influences in an innovative way.

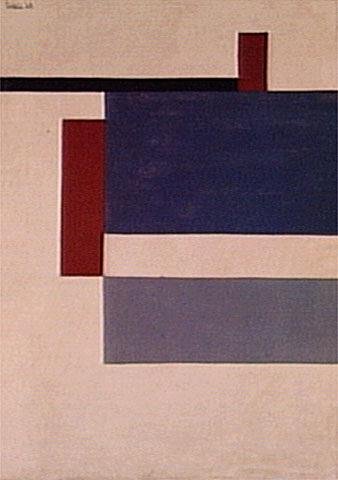

Even though Villa La Roche was completed in 1925, the same year as the Exposition Internationaledes Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris, it stands as a manifesto of minimalist andmodernist architecture. Its geometric rigor and stripped-down aesthetic stand in stark contrast to thedecorative exuberance of 1920s Art Deco, yet offer an ideal setting for the display of Concrete andNeo-Concrete Brazilian artworks.

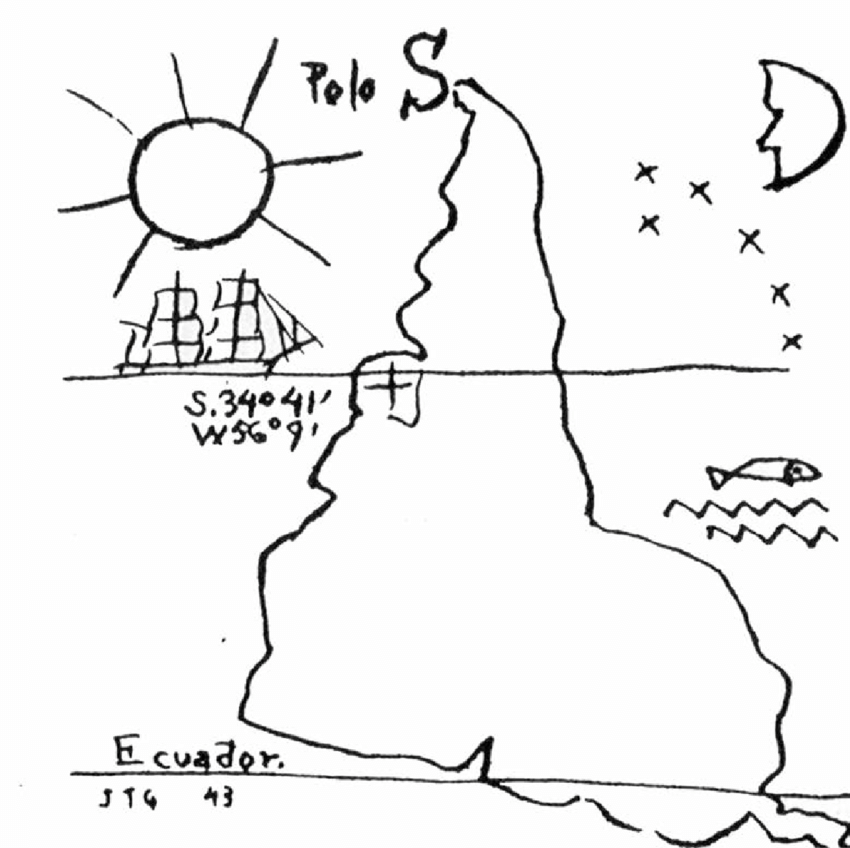

This constant exchange of influences between Brazil and France, recurring in different historicalperiods, not only enriched both aesthetics, but also played a fundamental role in the construction ofan identity of its own, as widely claimed both in the Anthropophagic Manifesto and, in the 1950s, in theconcept of Our North is the South. The latter proposed an inversion of the traditional geopolitical andcultural hierarchy, repositioning the South as the center of creation and thought, allowing a break withthe Eurocentric vision of art and culture and claiming an autonomous identity for Latin America.

The São Paulo Biennale, held since 1951 and inspired by the Venice Biennale, consolidated the city asan important center for international art. The event attracted renowned French artists such as HenriMatisse, Georges Braque, André Masson and Fernand Léger, promoting significant artisticexchanges.

Concrete Dialogues: From Van Doesburg tothe São Paulo Biennale

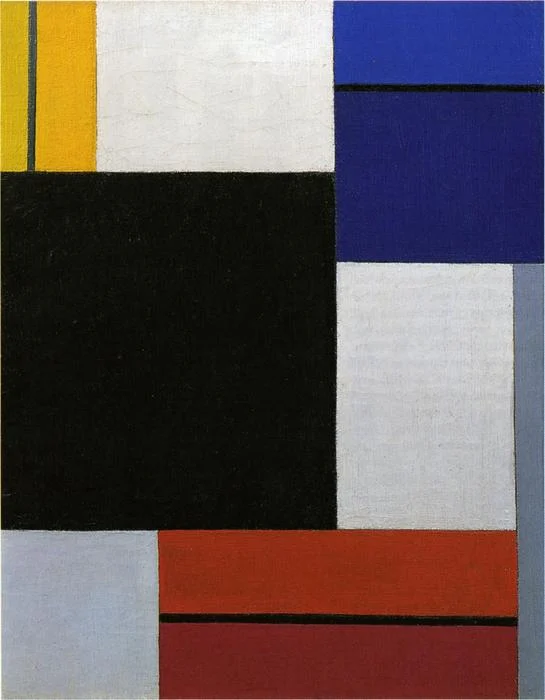

Max Bill’s arrival at the 1st São Paulo Biennial in 1951, with his sculpture Tripartite Unit, 1948, wasdecisive in boosting the concretist movement in Brazil. However, although he is the most recognizedname, other French artists also exerted a fundamental influence, such as Theo van Doesburg andAuguste Herbin.

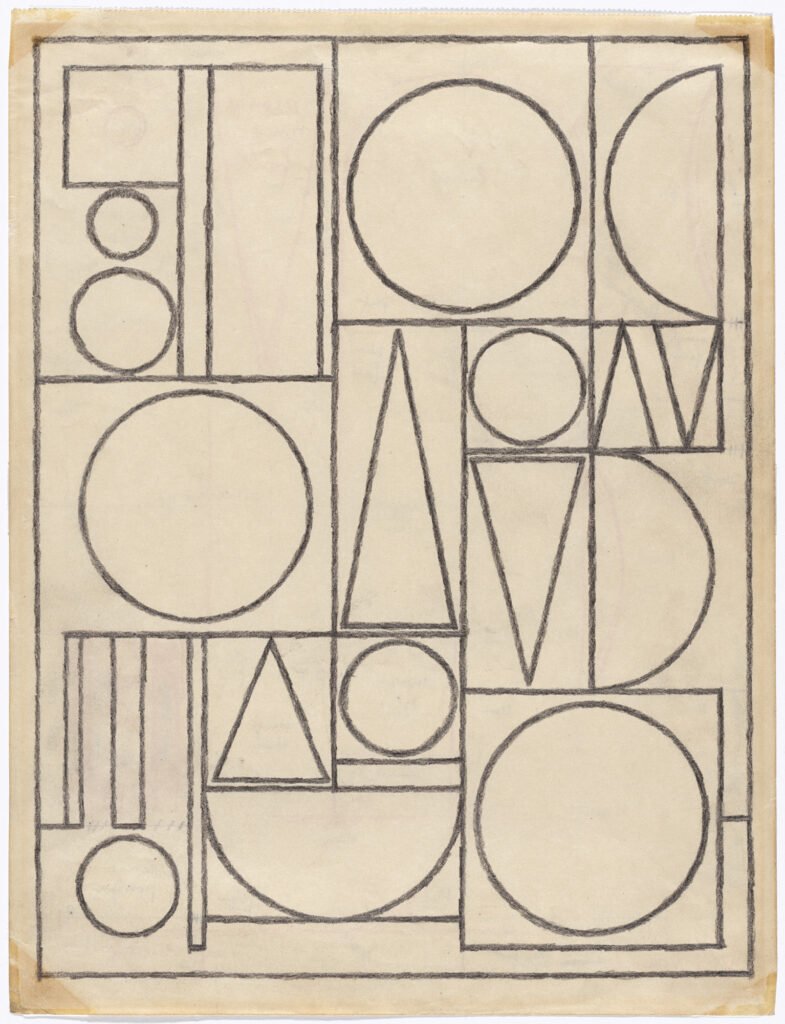

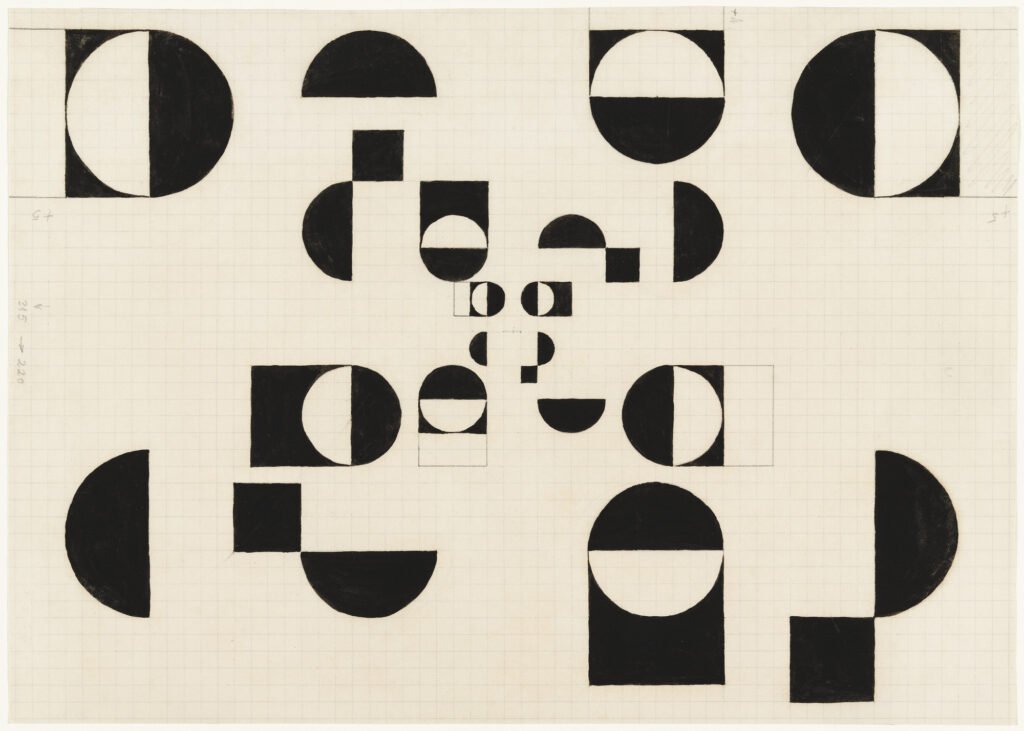

Van Doesburg, founder of the De Stijl movement, theorized “Art Concret” in 1930, laying thefoundations for concretism, while Herbin developed an innovative geometric and chromatic system,anticipating principles adopted by the Brazilian concretists. Although Herbin never visited Brazil, hisinfluence occurred indirectly, mainly through the dissemination of his ideas and works in Europe,where Brazilian artists in training had contact with his geometric approach and color system. Thisartistic exchange demonstrates the constant dialog between Brazilian production and the Europeanavant-garde.

By 1952, Brazil was ready to absorb this abstract avant-garde. In São Paulo, the Ruptura Group, led byWaldemar Cordeiro and Geraldo de Barros, consolidated concrete art. Two years later, in Rio deJaneiro, Ivan Serpa founded the Frente Group, bringing together artists such as Lygia Clark, HélioOiticica and Lygia Pape, who expanded the possibilities of concretism.

Thus, although Max Bill was a catalyst, Brazilian concretism developed within a broader context,rooted in the structural and chromatic principles of Van Doesburg and Herbin, consolidating Brazil asan essential pole of concrete art outside Europe.

This dynamic exchange between Brazil and Europe was not limited to theoretical or stylisticinfluences. It also unfolded through concrete opportunities for visibility and circulation of Brazilian artabroad. Well before the 1951 Biennial, Brazilian artists had already established connections with theFrench art scene. Academic painters such as Victor Meirelles, Pedro Américo, and Eliseu Viscontiexhibited at the Paris Salon, while modernists like Anita Malfatti, Tarsila do Amaral, Vicente do RegoMonteiro, Cícero Dias, and Candido Portinari deepened this presence in the early 20th century,engaging directly with European avant-gardes.

By the 1950s and 60s, these ties deepened with the growing international interest in concrete andkinetic art. Parisian galleries—particularly Galerie Denise René—played a key role in introducingBrazilian artists aligned with these movements to European audiences. A landmark example was the1964 exhibition Mouvement 2, which featured works by Lygia Clark, Sérgio Camargo, and otherinternational figures engaged with ideas of movement and perception. Far from being mere followersof European trends, these artists affirmed Brazil’s place as a vital force within the global concretistdialogue.